Twenty Years After Katrina—A Scientific Reckoning with Louisiana’s Vanishing Coast

By Micah Denesse

Twenty years have passed since Hurricane Katrina made landfall, and the scars it left on Louisiana’s coast remain both visible and deeply embedded in our collective memory. As a native of Plaquemines Parish, I have witnessed firsthand the transformation of our coastal landscape, from a thriving ecosystem and cultural stronghold to a region increasingly defined by loss and vulnerability.

My family has lived in Plaquemines Parish for generations. We have fished both commercially and recreationally, hunted waterfowl in the marshes and contributed to the development of original waterway maps near Buras and the east bank. Our heritage is literally inscribed in the geography; Bay Denesse bears our name, a testament to our enduring connection to the land and water. This is not merely anecdotal; it is emblematic of the deep interdependence between coastal communities and the ecosystems that sustain them.

Before Katrina, the marshes of Plaquemines were vibrant and productive. Duck blinds stood in areas now submerged. Fishing camps that once served as seasonal hubs for families and local economies have disappeared, as if erased from existence. The loss of these physical landmarks is not just symbolic – it reflects the accelerating rate of land subsidence, saltwater intrusion, and erosion that has plagued our coast for decades.

The storm was a turning point. Being on the ground in the immediate aftermath of Katrina revealed the fragility of our coastal infrastructure and the urgent need for restoration. It catalyzed my lifelong commitment to coastal advocacy, grounded in both personal experience and scientific understanding.

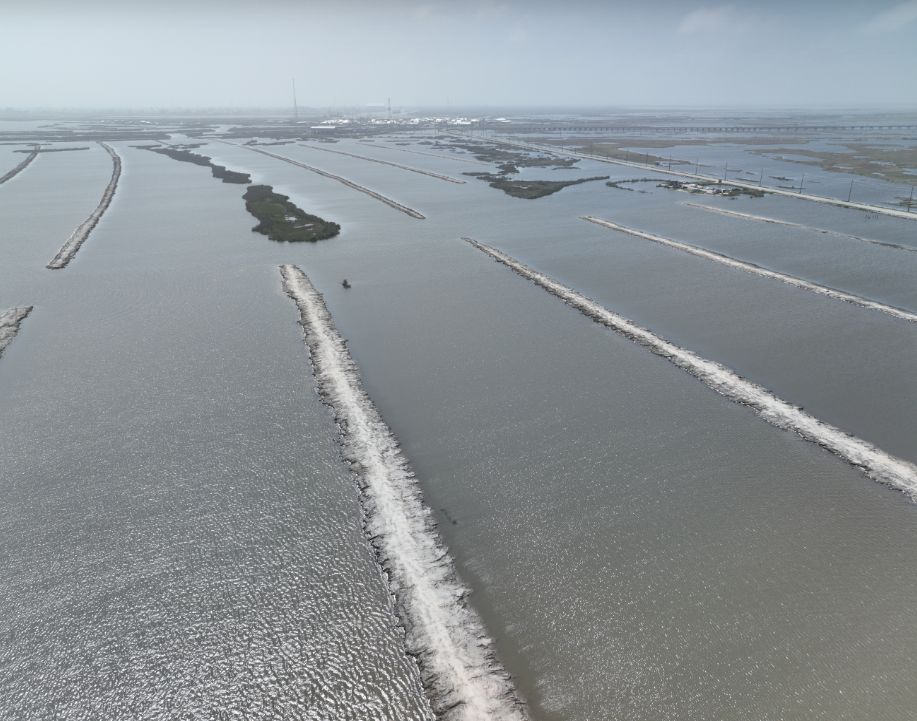

Organizations such as Ducks Unlimited have played a critical role in advancing restoration efforts. Their marsh terracing project in Port Fourchon, which added over 87,000 feet of terraces and 4,000 feet of living shoreline, exemplifies the application of ecological engineering to enhance sediment retention and habitat resilience. Similarly, levee construction at White Lake and habitat restoration at Pointe aux Chenes Wildlife Management Area are restoring hydrologic function and biodiversity across thousands of acres.

However, recent decisions by the state government have undermined this progress. The termination of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion Project—a $3 billion initiative designed to reconnect the Mississippi River with the Barataria Basin—represents a significant setback. This project was not merely a restoration effort; it was a cornerstone of Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan, backed by decades of sediment transport modeling, ecological forecasting, and stakeholder engagement. Its cancellation signals a troubling shift away from science-based policy toward short-term economic interests.

This moment demands reflection and recommitment. The 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina should serve not only as a memorial but as a scientific and civic imperative. We must recognize that the loss of coastal land is not inevitable; it is a function of choices. My family lost our way of life. My friends lost their homes, their possessions, and in some cases, their lives. If these losses are not sufficient to continually galvanize action, then we must ask: what will be?

Coastal restoration is not a luxury—it is a necessity. It is the foundation of our ecological integrity, economic stability, and cultural survival. Let this anniversary be a call to elevate science, honor heritage, and demand accountability. The future of Louisiana’s coast depends on it.